They shoot new media art when it grows old, don’t they?

People, institutions, and practices in the transitional decade of the 1980s.

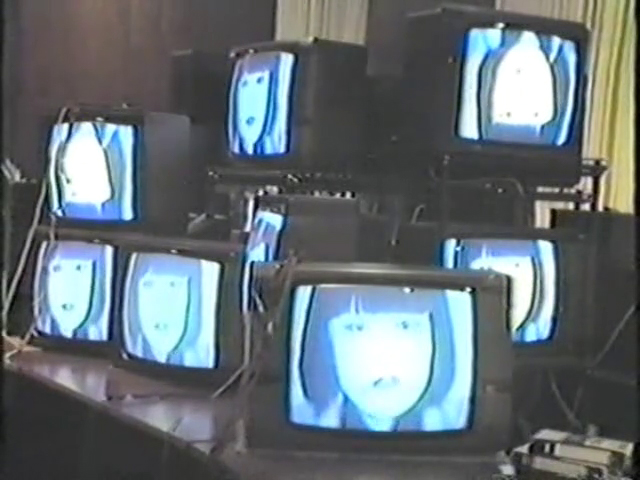

Nikos Giannopoulos, BABEL, 1983, Video installation

Video still from video documentation of the installation displaying Patrick Prado’s L’amour Transcode

Courtesy of the artist

Ambivalences

Would it ever be possible to write an art history of new media art in Greece? Such an undertaking would be faced with the very ontology of the artwork, as well as the incomplete inclusion in the canon of artists and artistic practices in our country between the late 1960s and 1990s. The term ‘new media’ itself covers a wide range of practices that, depending on the period, the artist, or the context of presentation, may refer to digital art, electronic art, computer art, art-and-technology, video art, video installation, and media art. The point of this classification surge, which is not limited to the Greek bibliography, is to identify and describe a medium’s specific characteristics in accordance with the academic field of art history. The adoption of a term brings forth certain historical narratives, focused on particular artistic practices, while excluding others. The term new media, which, because of its temporal designation, has been the focus of criticism in the international discourse, covers many different media and practices not directly related to one another.

The term has many, often contradictory, meanings. One possible definition is the following: New media art is the widely considered insufficient term for artistic engagement with emerging media within a theoretical framework in which art, science, and technology coexist. A core element of the new media theoretical framework is the recognition that artworks, artists, and practices in the shared field of art and technology have remained outside the historical canon due to various forms of bias. Today, our broader understanding of what constitutes art and artistic practice allows us to employ the field’s historiographic tools to individually or collectively retrieve, restore, and reconstruct works by drawing on knowledge not only from art but also from science and technology. For Greece, where the history of the recent past remains still to be written, the inclusive field of new media may allow us to put together a new historical narrative of artistic practices, but also an artistic and critical discourse that combines art and technology, by examining artworks and artists that have systematically remained outside art history.

The Greek dictatorship’s impact on the development of Greek television is a distinct issue in the spread of new audiovisual technologies. Regular television broadcasts in Greece began in 1966, just one year before the coup. For the following seven years, the state television service, the only one available in the country, operated under the supervision of the Ministry of National Defence, which reinforced the station’s infrastructure due to its propaganda potential. Even soap operas sought to cast military men in a positive light, portraying them as incorruptible heroes in positions of power. Every aspect of production underwent censorship. In this bleak and stifling climate, the subversive and liberating potential of the new medium of television could not be artistically harnessed. The corresponding critical and theoretical discourse never developed for the same reasons. 1

When I began researching and writing the history of new media art in Greece a decade ago, I came across two basic obstacles.

The first one was that many artists who had used new technologies to create their works from the 1960s onwards were, for various reasons, absent from the canonical texts of Greek art history. The second obstacle was that the texts that could be described as canonical, in that they sought to include all or a part of the history of art in Greece, were very few. Furthermore, while in the last decade, there has been an abundance of texts on the recent history of art in Greece, I began to notice a third obstacle as I pursued my own research to identify artists excluded from canonical texts: a certain ambivalence on the part of institutions, art history, and, especially, artists themselves towards artworks created with new media. This meant that the absence of references to these works was not invariably the result of rejection, the inability of institutions to support exhibitions, a lack of know-how or theoretical background among critics of the time, or because they were the works of unknown visual artists. In addition to all these reasons, many artists kept those works out of the core of their oeuvre and did not regard them as autonomous artworks at the time; some were never even exhibited.

Through a number of different routes and through systematic research for my doctoral dissertation, I began to notice a series of events that formed an alternative narrative of the history of new media in Greece.2 This new narrative begins in the late 1960s with the mathematical-technological allusions of Pantelis Xagoraris and with the sculptor Theodoros’ critical engagement with new mass media in his Manipulations series (1973–1982). Several artists also kept their significant experimental audiovisual works separate from their general practice and would often present them to select audiences many years later. This was very much the case with Aspa Stasinopoulou’s films, some of which were shown 30 years later.3 Equally, Dimitris Alithinos’ films and videos, made in the 1970s, were presented for the first time in his retrospective exhibition at ΕΜΣΤ | National Museum of Contemporary Art, Athens, in 2013.4 Likewise, the politically engaged work Bouboulina (1981) by Leda Papaconstantinou and Carole Roussopoulos has been shown only once to date.5 This ambivalence is present in the way Theodoros describes his work Tele-manipulation, part of “The Creators” series produced by Giorgos Emirzas, without actually calling it a work of art: “The two films (parts 1 and 2) form a diptych, there are analogies in the way they have been put together as well as contrasts. Although they are ‘documentaries’ of my work, their plot is such as to constitute an expression analogous to that of the works being presented.”6

2. Theodoros, sculptor, Tele-manipulation, 1976

16 mm film, black and white, with sound, 53΄

EMΣT Art Archive; courtesy of ERT Archive

People

From 1980 onwards, the discourse on art and technology has been destigmatised and broadened by a group of artists from disparate fields, including the visual arts, music, dance, architecture, television, and cinema, mainly through the application of video technology in art. This shift is part of the dense politico-ideological environment of “Change” under the first PASOK government. More specifically, it is linked to the ideological shift towards young people, promoted systematically at the time through the General Secretariat for Youth, the emergence of linguistic idioms used by younger people, and the emergence of video and private television as an alternative to the state monopoly on home entertainment and information.

These artists included Dimosthenis Agrafiotis, Tassos Boulmetis, Yioulia Gazetopoulou, Nikos Giannopoulos, Alexandra Katsivelaki, Pandora Mouriki, Margarita Ovadia, George Papakonstantinou, Aris Prodromidis, Lucia Rikaki, Manthos Santorineos, Angelos Skourtis, Eva Stefani, Marianne Strapatsakis, Marianna Theodoridou, as well as the artist couple Thanasis Chondros and Alexandra Katsiani, together with their music/art group ‘Dimosioypalliliko Retiré’ (i.e., ‘Public Sector Worker Penthouse’) along with Ntanis Tragopoulos. Alongside them are the considerably older painter and engraver Nestoras Papanicolopoulos, who rekindled the debate of computer use in artistic creation, and Mit Mitropoulos, with a significant contribution to art through telecommunication networks.

2. Marianna Theodoridou, Allegories, 1984

Video, colour, with sound, 6΄

Courtesy of the artist

As was also the case with the mythical, oral narratives in the experiments of Nam June Paik, Andy Warhol, and Wolf Vostell, which have been constantly contested, rewritten, and reinterpreted, the first-ever experiments in Greece are claimed by many artists who regard themselves as pioneers in the use of video. All such claims can be regarded as valid, but they involve perspectives on artistic practices structured by different terms, interpretations, and hierarchies. As is often the case in the history of technological media, there is scarce documentation and critical references on the first artistic uses of video. Several original artworks have also been lost or destroyed due to indifference, a lack of technical know-how, or shifts in audiovisual technology.

Yioulia Gazetopoulou’s work is a case in point. She is often mentioned as one of the first artists to use video technology at an event at Polyplano Gallery in 1977–1978.7 In most cases, this is mentioned as something having happened in the recent past, yet no contemporary reference from that time, with details about the space and the performance itself, is available.8

Similarly, there is scant evidence regarding Mit Mitropoulos’ Mail Art exhibition at the Gazette bookstore, where, among the exhibits, he presented a television screen tuned to show static at all times except the hour of a television show on the exhibition itself. This gesture, which is part of Mitropoulos’ overall telecommunication artistic practice, is dated to 1978, but references to it appear several years later.9 The same applies to the Face to Face installations that were presented in Salerno, Italy, and at the exhibition Artcom in Paris in 1986, as well as at the V2 Center in ‘s-Hertogenbosch, the Netherlands, in 1989. In this series of installations, two individuals communicate face to face through different levels of remote audiovisual communication technology, including slow-scan image transmission via telephone line or a two-way cable television circuit. The visible part of the installation, each time, consisted of two television sets displaying two faces speaking to one another.10

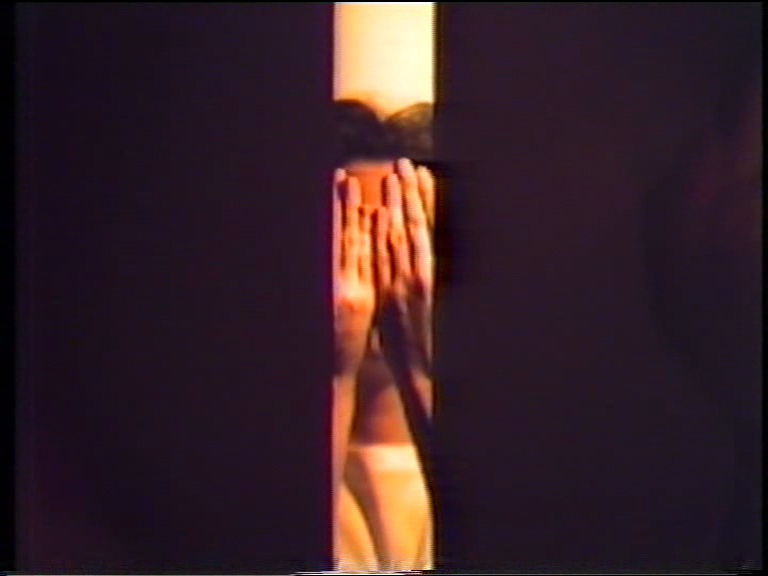

In 1981, Leda Papaconstantinou, in collaboration with Carole Roussopoulos, produced the video Bouboulina on the island of Spetses. In this video, women from different generations speak about Bouboulina as part of the island’s living history. Through targeted questions, episodes from Bouboulina’s life unfold in parallel to the contemporary everyday lives of the island’s women. The film belongs to the style of Carole Roussopoulos’ engaged documentation, with images of Bouboulina overlaid on those of the participants as they go about their everyday activities, such as embroidery, the camera often focusing on their hands as they speak.

2. 3. Leda Papaconstantinou and Carole Roussopoulos

Bouboulina, 1981

Video, black and white, sound, duration 30΄ 30΄΄

Direction and production: Leda Papaconstantinou and Carole Roussopoulos

Editing: Carole Roussopoulos

Edition: 1/5 + 2 AP

Courtesy of Leda Papaconstantinou, Alexandra Roussopoulos and Geronimo Roussopoulos

In the early 1980s, video equipment was rare and expensive, especially compared to film, which was more widespread and persisted as the norm for documenting artistic activity in Greece. Nevertheless, video possessed two distinct characteristics that made it highly desirable for artists: first, a television monitor could be placed in an exhibition space alongside other visual artworks, unlike film, which required its own dedicated dark space; and second, video could be used in the exhibition space straight after recording, whereas film had to be processed. Aris Prodromidis made use of both advantages in the recording and presentation of the installation/performance Act III, which he carried out in 1981 at the exhibition Environment–Action, organised by the Association of Greek Art Critics. In this work, Prodromidis turned the spotlight on the figure of the artist by staging his everyday life in his studio, surrounded by his equipment and work. Part of the performance was recorded on a video set on playback during the artist’s absence from the space.11 The same year, Prodromidis held a mixed-media exhibition, Anamorphosis, at Medousa Art Gallery, featuring mostly anamorphically transformed photographic portraits. The exhibition also included his first autonomous video, titled Anamorphosis (1981), which showed anamorphic distortions of his face on a reflective, distorting surface.

Aris Prodromidis, Self-portrait/Anamorphosis, 1981,

single-channel video, 7:25, EΜΣΤ collection

In 1983, Angelos Skourtis, in collaboration with Li Likoudi, presented the composite performance National Garden, in which the artists placed rectangular coloured plexiglass and canvases marking viewing points in the National Garden of Athens. During the show’s opening, a flautist led visitors from the National Garden to the Desmos Art Gallery for the continuation of the exhibition, which included photographic collages, photographs from the intervention, and a video. In the video, titled Metaplasis (1983) and described in the press release as a “body art performance”, foliage was projected onto naked bodies. In this work, the use of video enabled projection of images from the familiar device of television, allowing it to function as a commentary on the technological mediation of the experience of nature, which was also the theme of the performance.12

The first documented hybrid video-performances also took place during the same period. In 1983, Nikos Giannopoulos collaborated with dancer Nena Papageorgiou and pianist Thomas Sliomis to present the performance Before 1984 or Illusions at Polyplano Gallery. The 45-minute performance was repeated 15 times in the gallery that had been arranged like an apartment: one section was taken up by the piano, while the choreography unfolded mostly in another section as the audience moved freely through the space. The walls of the rooms were covered with mirrors with rounded corners to resemble television screens. Among them, actual television sets played random advertisements, music videos, or closed-circuit images from a video camera operated by Nikos Giannopoulos. The performance was a comment on the crisis of personal identity in an environment saturated by mass media and information. This critique was expressed through Nena Papageorgiou’s choreographic dramaturgy, in which she abruptly assumed different stereotypical roles. The network of screens, mirrors, and Giannopoulos’ camera enabled observation from every angle in the space.

In 1985, Marianne Strapatsakis presented a series of paintings on reflective metal surfaces at Medousa Art Gallery. With the intention of capturing the temporal element of light reflection in her works, she began work on the video Vital Pulses (1985), in collaboration with musician Thanasis Zlatanos. This work was first presented as part of an installation accompanied by a live musical performance by Zlatanos at the Praxis Festival of the Goethe-Institut Athen in the same year. Later, a single-channel version of the video was presented as an autonomous work of art in the first group video exhibitions at Studio Videograph in Thessaloniki and at the 1st Document exhibition at Gallery F in Athens in 1986.

Marianne Strapatsakis, Vital Pulses, 1985

Video, colour, with sound, 5:15

Courtesy of the artist

In 1985, Costas Tsoclis also made a significant contribution to video art practices with Harpooned Fish, a video installation presented in his solo exhibition at Zoumboulakis Gallery. The work consists of a half-painted canvas with a spear fixed at the centre, onto which the image of a speared fish is projected. Tsoclis termed “Living Painting” the completion of the painted image through video projection. One year later, the artist presented a cycle of five portraits of a similar technique, together with Harpooned Fish, as part of the Greek representation at the Venice Biennale. The case of “Living Painting” is an exception both because of the use of video by an already established artist and the work’s presentation in established institutions.

Alexandra Katsivelaki’s work was featured in almost every video art presentation in the second half of the 1980s. Her works emerged from recordings of television monitors via a closed-circuit camera and other imaginative ways of distorting the image using basic technological means. Her work, for which she collaborated with electronic music composers, takes a sensual approach to sound and image. Katsivelaki is among a few Greek artists who have focused on the structural elements of the video medium.

Another special case of an artist who went beyond the simple production of individual artworks is Margarita Ovadia. She worked as a television director on programmes such as Chromata [Colours] by Lucia Rikaki, but was also involved in artistic events, including the 1st European Meeting on Art/New Technologies. Her works include video dance experiments in collaboration with Mahi Dimitriadi, such as 20,000 Leagues Under… (1989), as well as the video Cyaniris (1987), made in collaboration with the pioneering composer Lena Platonos, which also functioned as the music video of Platonos’ same-titled electronic composition.

Institutions

The period’s institutional field was shaped by artistic or other private initiatives that furnished occasional support. Already since the dictatorship, spaces such as the Athens Technological Institute launched by [Constantinos] Doxiadis Associates, the Goethe-Institut Athen, and the pioneering Desmos Art Gallery were instrumental in supporting new artistic media. Although television had evolved during the dictatorship, this was not true of the related medium of video, which would evolve in the following decade.

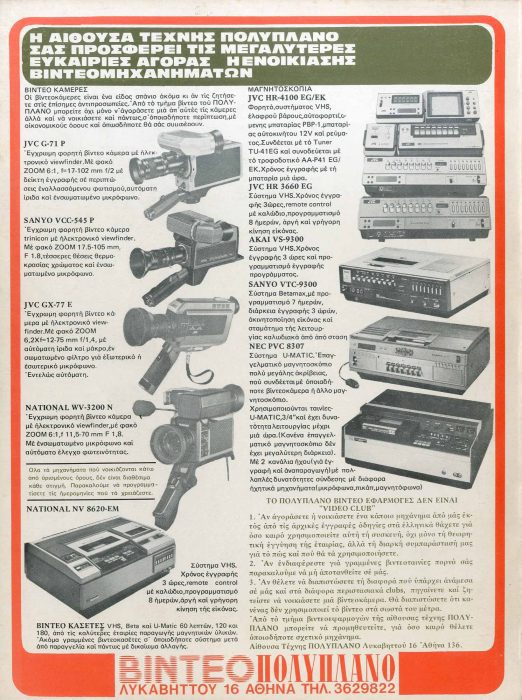

In the 1980s, Polyplano Gallery and SIMA art magazine (both under the direction of Nikos Papadakis, who saw video as a new popular art) became particularly active in the field of video.13 Seeking to support the new medium, he organised screenings of video works by mostly American pioneers and provided equipment for shooting and editing video for artistic use.14 Video began to appear in shows held at commercial galleries such as Medousa and Desmos, as well as in short-lived new spaces or occasional events without institutional support. Among the exceptions was ERT [Hellenic Broadcasting Corporation], which in 1984–1985 financed and presented Nikos Giannopoulos’ programme Video Art that played a pivotal role in the small-scale production of new works of the period; the 28th Thessaloniki Film Festival in 1987, which held a special series of events on video art; and the 2nd Biennale of Young Artists from Europe and the Mediterranean, held in Thessaloniki in 1986 with the support of the General Secretariat for Youth.15

Mikro SIMA, issue 1, February 1981

Back cover page advertising available video equipment at Polyplano Gallery

The first institutions and art spaces specialising in new media emerged in the 1990s, when foundations, institutions, and commercial spaces reshaped the landscape of contemporary art in Greece, and included the Ileana Tounta Contemporary Art Center, with a specialised Art and Technology department under the direction of Manthos Santorineos, and Fournos Centre for Digital Culture, again under the direction of Manthos Santorineos, here along with Dodo Santorineou, which is still in operation. A new generation of visual artists claimed their place through the use of new technologies, while the majority of the 1980s pioneers withdrew from the scene, and their contributions soon fell into oblivion.

Theory and curating

In the 1970s, discourse on new media emerged from individual artists who pursued entirely different practices, while their works are predominantly presented in their solo exhibitions. In the early 1980s, most artists worked in relative isolation from one another, oblivious of other artists in Greece using video or other new technologies. This changed with the first group exhibitions and presentations that sought to bring domestic production together. One landmark event was the first television programme about video art on Greek television, produced by Nikos Giannopoulos in 1984–1985 and titled Video Art. In a series of six episodes, Giannopoulos presented works by Patrick Prado, Dominique Belloir, Walter Verdin, Albert Pepermans, Pieter Vereertbrugghen, and Ann Francx. He also sought work by Greek artists, encouraging and supporting some in their first video work. Works by Tassos Boulmetis, Alexandra Katsivelaki, Manthos Santorineos, Leda Papaconstantinou, and Nikos Giannopoulos himself were presented through the Greek television network, along with Nestoras Papanicolopoulos’ electronic painting.16

The reception of new technologies at the 28th Thessaloniki Film Festival in 1987 was also an important event. It featured a special focus on video art in Greece with an exhibition, discussion, and screenings that included works by Greek artists mostly produced outside Greece. The event included works by the architect George Papakonstantinou, the film director Tassos Boulmetis, and the visual artists Aris Prodromidis, Marianna Theodoridou, Leda Papaconstantinou, Marianne Strapatsakis, and Manthos Santorineos, as well as the music/art group Dimosioypalliliko Retiré (Thanasis Chondros, Alexandra Katsiani, and Ntanis Tragopoulos), and others.17

George Papakonstantinou, Ce qui se passe, quand il ne se passe rien, 1986

Video, colour, with sound, 16:10

Courtesy of the artist

A week of events dedicated to art and technology, titled Art without Borders and organised by Manthos Santorineos, was held at the Ileana Tounta Contemporary Art Center in 1989. It included works beyond electronic images and video, using lasers, holography, robotics, and electronic sound, among others.18 In the same year, a video art exhibition and a tribute to art and technology were held within the 4th International Festival of Patras.

These events were mainly educational in nature. Their purpose was to familiarise the public with video art and technology, its main representatives in Greece and abroad, and its differences to cinematic language, rather than to attempt a broader classification, analysis, or critical evaluation of the work.

In 1990, Nikos Giannopoulos, George Papakonstantinou, and Nikos Patiniotis organised the 1st European Meeting on Art/New Technologies. The festival included more than 300 works, videotapes, and video installations. This was the largest event on art and technology ever to take place in Greece, bringing together issues such as production, screening, and distribution that had preoccupied new media artists in Greece for a decade.

Beyond artistic ambivalence, it is also important to mention a corresponding ambivalence among critics, curators, and art historians of the 1980s towards art and technology. A characteristic example is the text for Aris Prodromidis’ solo exhibition at Medousa Art Gallery in 1981, the first exhibition with standalone video work in an Athenian commercial gallery, in which the author does not once refer to the medium itself.19 Eleni Vakalo is an exception who, in her four-volume work on postwar art in Greece refers, somewhat awkwardly, to Pantelis Xagoraris’ computer drawings and to video in the work of Yioulia Gazetopoulou and Angelos Skourtis/Li Likoudi as a means of documentation.20 The first curator to critically approach Greek visual/audiovisual production of the period through a theoretical perspective was Anna Kafetsi during the round-table discussion “Video Art in Greece”, held during the Art without Borders week at the Ileana Tounta Contemporary Art Center in 1989.21

Modernisation policies

Although some of the events that canonised video art occurred in and were indirectly supported by public cultural institutions (such as ERT and the Thessaloniki Film Festival), there was no specific state cultural policy for visual/audiovisual artistic production. An exception was the General Secretariat for Youth. Support for the creative use of technology was part of a broader discourse that identified technology with progress and economic development within the policies of the political movement of “Change” and the ideological constructs of youth and technology, as noted by Argyri Katsaridou in her dissertation on photography.22

The General Secretariat for Youth of Andreas Papandreou’s first government was tasked with coordinating government policy for young people and supported youth creativity through new technologies, organising several events during the 1980s. Among them were the 1984 conference “Youth and Language” and the 1987 conference “Art and Technology”, the second held in collaboration with the Technical University of Crete in Chania featuring presentations from various cultural fields, but with a special emphasis on the uses of technology within creative industries such as fashion and architecture 23

The link between youth and technology was only one way of conveying the idea of progress, since both are driving forces of social change. Unfortunately, as art historian Argyro Katsaridou notes regarding photography, such claims did not become policy but instead functioned mostly as a means of promoting the idea of progress for political purposes.24

Whenever cultural production serves political purposes, even occasional support can lead to significant changes. A case in point is the 2nd Biennale of Young Artists from Europe and the Mediterranean, held in Thessaloniki in 1986. This was an important artistic event with more than 350 participants from disciplines such as architecture, fashion, dance, music, comics, cinema, photography, industrial design, theatre, literature, jewellery-making, and video art. It was the first major event of this nature to include a distinct video art section, with works by Tassos Boulmetis, Damianos Georgiadis, Konstantinos Kapetanidis, Giannis Kouitzoglou, Vangelis Moladakis, Dimitris Mourtzopoulos, Margarita Ovadia, Marinos Pasaloudis, Nikos Patiniotis, and Konstantinos Stratoudakis. The inclusion of video as a distinct section is an indication of its position at the time, though the inclusion itself is also noteworthy. Participation in each biennale section was determined by separate special committees, and a member of the video art section’s committee was the architect and artist Mit Mitropoulos, who also oversaw the implementation of this section’s “special project”, The Line of the Horizon.25 This unique project involved a fax network between 27 locations arranged from east to west around the world: from a tanker in Hormuz Straits of the Persian Gulf, to Limassol in Cyprus, Alexandria in Egypt, Rhodes, Heraklion, Chania, Milos, Chalcis, Volos, Athens, Kalamata, and Patras in Greece, Valletta in Malta, Tunis in Tunisia, Naples, Rome, and Turin in Italy, Nice, Marseille, and Montpellier in France, Barcelona in Spain, a bulk carrier ship in the port of Lisbon in Portugal, a houseboat on the Maas River in the Netherlands, Toronto in Canada, and New York in the USA.26 This unique undertaking is still absent from critical and theoretical discourse as well as from recent art history in Greece. Similarly, the significance of the 2nd Biennale itself has not been assessed, even though it gathered and presented a generation of emerging artists who shaped art in Greece in the following decades in every field.

Mit Mitropoulos, The Line of the Horizon, 1986.

On the left is Mit Mitropoulos, on the right a Toshiba technician, and between them a fax machine. From the activation of the The Line of the Horizon network.

2.

The Line of the Horizon: “Network reach, longitudes, latitudes, footprints of satellites”.

From Mit Mitropoulos, “Geopolitical art: The aesthetics of networks”, Ekistics, Vol. 55, No. 333, Aesthetics (November–December 1988), pp. 307–314.

The first private television channels began broadcasting in Greece in 1989. This was a landmark event that abruptly and radically changed the mass communications sector in Greece, while also bringing major transformations in culture and, of course, in the field of audiovisual production. The field was further transformed during the 1990s by the following factors: the establishment of the first private foundations (such as the DESTE Foundation); the emergence of a younger generation of artists who created, exhibited, and sold video artwork; and the gradual turn of a previous generation of artists, who had fought for the visibility of the medium, to other professional fields made available in education and the new private television channels. Special mention should be made of the operation of Fournos Centre for Digital Culture from 1992 onwards, which enabled the emergence of a systematic discourse on art and technology during a period of globalisation.

With today’s theoretical tools and a broadened understanding of what constitutes an artwork and artistic practice, and freed from the allure of technological novelty, we can proceed to a different evaluation of new media art between 1970 and 1990. This will allow us to place it within the wider framework of art history and the histories of new media, both locally and globally.

Thanasis Chondros and Alexandra Katsiani, Writing, 1987

Video installation, colour video with sound, monitor, pedestal, pencil shavings, duration 14:04 (looped)

ΕΜΣΤ Collection, donated by the artists

See Stathis Valoukos, The History of Greek Television, Athens: Aigokeros, 2008, p. 53; also, Sotiris Maniatis’ article on Greek television during the dictatorship, Εfimerida ton Syntakton newspaper, 20–21 April 2013 [both in Greek].

These include the research for the exhibition The Years of Defiance: The Art of the 70s in Greece, 2005, the ΕΜΣΤ | National Museum of Contemporary Art, Athens, curated by Bia Papadopoulou; the exhibition Bia Davou: A Retrospective, ΕΜΣΤ, 2008, curated by Tina Pandi and Stamatios Schizakis; the exhibition Dimitris Alithinos: A Retrospective, ΕΜΣΤ, 2013, curated by Tina Pandi and Stamatios Schizakis; the exhibition PLEXUS Petros Moris – Bia Davou – Efi Spyrou, 2015, House of Cyprus, curated by Tina Pandi and Stamatios Schizakis; the screening programme Terrhistories–Greece, as part of the 26th Festival Les Instants Vidéo in Marseille, 2013, curated by Stamatios Schizakis; the programme @postasis and the Tribute to Pantelis Xagoraris, Athens School of Fine Arts, 2020, presented by Stamatios Schizakis, Manthos Santorineos, and Stavroula Zoi. The doctoral dissertation at the University of Sunderland was completed in 2022, under the supervision of Alexandra Moschovi and Beryl Graham, entitled “Plugged In: The Introduction of New Media Art Practices in Greece in the 1970s and 1980s”.

Such as the work The Surgery (1972, coloured film with sound), presented at the exhibition The Suffering Body in 2004.

The works Colour, Psychological Stimulation. Patra-Ancona (1976, 8 mm coloured film with sound, 3:36), Self-Portrait (1974, 8 mm coloured film with sound, 1:22), Avantgarde and Tradition (1974–1975, 3 black and white videos, with and without sound, 2:52, 2:23 & 3:52) presented at the exhibition Dimitris Alithinos: A Retrospective in 2013, curated by Tina Pandi and Stamatis Schizakis.

In Leda Papaconstantinou’s retrospective Time in my Hands, in 2023 at ΕΜΣΤ, curated by Tina Pandi.

SIMA art magazine, issues 19–20, September–December 1977, p. 18.

References to Gazetopoulou’s work include the following: George Papakonstantinou’s text, “La busca de identidad del videoarte griego”, in Pérez Ornia & José Ramon (Eds.), Televisión y video de creación en la Comunidad Europa, catalogue of the exhibition Panorama Europeao del Videoarte, Madrid, 1992, p. 220 [in Spanish]; the catalogue of the 1st European Meeting on Art/New Technologies (edited by Nikos Giannopoulos, George Papakonstantinou, and Nikos Patiniotis), Athens: ESTET, 1990, p. 84 [in Greek]; and the article by Lina Tsikouta, “Video”, Kathimerini newspaper, 6 February 2005 [in Greek]. In an unpublished interview, Giannopoulos says that Gazetopoulou’s action was carried out using an endoscope, although he himself was unable to confirm the date.

Undated references appear in the four-volume work by Eleni Vakalo, The Profile of Postwar Art in Greece [in Greek], as well as in the artist’s interview with Nikos Papadakis, published on the occasion of her exhibition at Polyplano in 1983: Eleni Vakalo, The Profile of Postwar Art in Greece: After Abstraction, Athens: Kedros, 1985, p. 111 [in Greek]; and Yioulia Gazetopoulou, Nikos Papadakis, Found Concept, Athens 1983, Polyplano Gallery.

Mit Mitropoulos, “Distance: Obstacle and Tool in the Process of Communication”, Eikastika, no. 47, November 1985, 40–41; and “Geopolitical art”, op. cit.

Mit Mitropoulos, “A sequence of video-to-video installations illustrating the together/separate principle, with reference to two-way interactive cable TV systems”, Leonardo, vol. 24 (1991), 207–211.

This later became a short video titled La Vita d’Artista (1981).

Desmos Art Gallery, Li Likoudi and Angelos Skourtis: Intervention – Action – Video (1983, press release).

In the sense of art that addressed the broader public but also gave voice to it.

Nikos Papadakis, Neo SIMA, no. 3, 1–11 February 1981, and Mikro SIMA, no. 1, February 1981 [in Greek].

Stefanos Tsitsopoulos, “2nd Biennale of Young Artists in Thessaloniki: I was there too”, Athens Voice, 1 June 2025, https://www.athensvoice.gr/life/poleis/907177/v-biennale-neon-kallitehnon-sti-thessaloniki-imoun-ki-ego-ekei/ [in Greek].

Nikos Giannopoulos, “Video Techni”, TV & Video, no. 16, May 1986 [in Greek].

Giorgos Baganas (Ed.), Video Art – 28th Thessaloniki Greek Film Festival, Thessaloniki, 1987 [in Greek].

Ileana Tounta Contemporary Art Center, Art without Borders – A week dedicated to art and technology, Athens: Ileana Tounta Contemporary Art Center, 1989 [event leaflet, in Greek].

Efi Strousa, Prodromidis, exhibition catalogue, Athens: Medousa Art Gallery, 1981 [in Greek].

Vakalo, op. cit., vol. 4, pp. 26, 111, respectively [in Greek].

Anna Kafetsi, “From the discussion about video art in Greece”, Spira, 3(1), Summer 1990, 165–169 [in Greek].

Argyri Katsaridou, “Photography in Greece 1970–2000: The development of the theoretical discourse and the institutions”, PhD thesis, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, 2010, pp. 136–150 [in Greek].

Calliope Rigopoulou et al. (Eds.), Art and Technology, Athens: Ypsilon books, 1988 [in Greek].

Katsaridou, op. cit., pp. 150–160.

Ministry of Culture, General Secretariat for Youth, Municipality of Thessaloniki, 2nd Biennale of Young Artists from Europe and the Mediterranean] Thessaloniki: Lexicon, 1986, p. 144 [in Greek].

Mit Mitropoulos, “Geopolitical art”, op. cit., p. 310.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Art historian, curator of photography and new media at EMΣT | National Museum of Contemporary Art, Athens, Stamatis Schizakis studied history and theory of art and photography at the University of Derby and art history at Goldsmiths College. He completed his PhD at the University of Sunderland, on the subject of the introduction of new technologies in art in Greece. He works as a curator at ΕΜΣΤ since 2005. He has curated the exhibitions: Theodoros, sculptor: In lieu of a Retrospective, 2025; Mikhail Karikis: Because we are together, 2023; PLEXUS Petros Moris – Bia Davou – Efi Spyrou, 2015 (co-curated with Tina Pandi); Dimitris Alithinos, A Retrospective, 2013 (co-curated with Tina Pandi); Phoebe Giannisi – TETTIX, 2012; Rena Papaspyrou, Photocopies straight through matter, 2011; George Drivas, (un)documented, 2009; Bia Davou, Retrospective, 2008 (co-curated with Tina Pandi). Since 2017, he realises the First and Last and Always Psiloritis Biennale.