Painting in Contemporary Art

Between the Market and Museums: Greek Realities

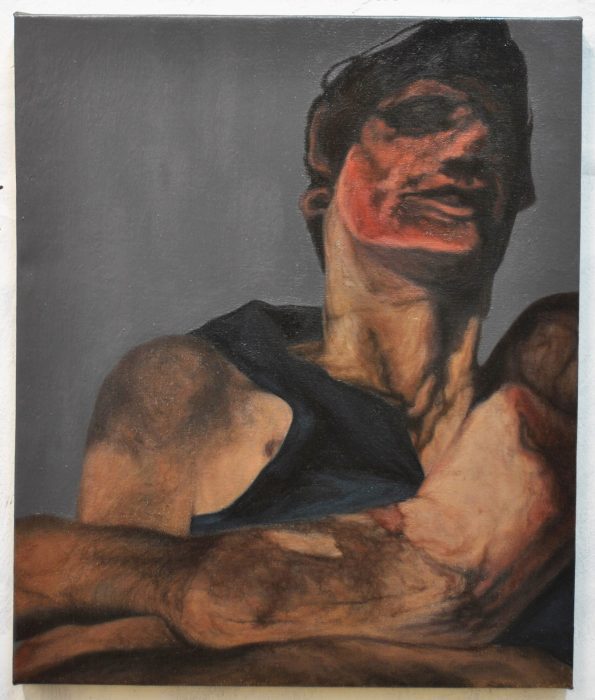

Sasha Streshna, In the woods, 2022

Oil on canvas, 155 x 230 cm

Courtesy of the artist

Photo Stathis Mamalakis

[Soundtrack: “God Save the Queen”, The Sex Pistols]

Khlebnikov: “In your opinion, what are the standards of our time?” Filonov replies: “Look, I did a painting and I want it to stay on the wall by itself, without nails.” […] Khlebnikov asks intrigued: “And how did that go?” “For the time being, I’ve stopped eating.” “And the painting?” “It keeps falling down. I spend the day looking at it, staring at it, talking to it. I say: ‘You stupid wall, what else do you want from me? You want Heaven to come and take me? Hold up the painting!’”1

Iconomy

[Everything flows (ta pánta rhéi), even the gaze.]

The concept of ‘iconomy’ proposed by the philosopher Peter Szendy in his book The Supermarket of the Visible (2019)2 can serve as a key for understanding the status of painting today – a status of some ambivalence: while still a dominant mode in private collections and commercial transactions, it is marginalised as a subject both of academic research and theory, and of museological appreciation and recognition, treated (as it is) as a separate formal category by contemporary art institutions.3 Szendy draws the term from Marie-José Mondzain,4 who analyses the image – in her book Image, Icon, Economy (2005) – via Byzantine theology: the image is not simply a representation but rather a mode of mediation – a mechanism for regulating flows of faith, power, and visibility between the human and the divine. The ‘iconomy’ of the image, then, concerns the regulation of our relationship with what we see and believe.

Szendy transfers this line of thought to the realm of late capitalist visual culture. In the world of social media, digital platforms, and the algorithmic logging of attention, the image has stopped being simply a mode of representation; images are peddled as products and valued as a kind of currency, accumulating worth through impressions, views, and likes. The gaze is no longer innocent; it is appraisable, exchangeable, part of an attention economy that determines what carries significance and what does not.

If we view painting through this prism, the reasons behind its ambivalent status within contemporary art become clearer. On the one hand, it resists both haste and the logic of exchange espoused by the ‘iconomy’, demanding slowness, a lingering gaze, presence instead – it is an ‘anti-iconomic’ act within a world oversaturated with images. On the other hand, it does not emerge unscathed: paintings too are sold as investments, traded as status symbols, reproduced on digital platforms, and incorporated into distribution networks.

Painting finds itself, then, both at the heart and on the margins of the contemporary ‘iconomy’, all at once: producing images not meant for consumption that are nonetheless, inescapably, consumed; resisting commercialisation while also being the commodity of the art world par excellence. It is amid this tension between the slowness of the gesture and the speed of visual circulation – between the gaze that holds and the gaze that is measured – that the relevance of painting is delineated today. A relevance reflected not just in the content but also in terms of form – its size, gestural nature, and physical presence.

A Slow Look at the Digital World

[Too slow for your feed?]

Thirty years have passed since Hal Foster pointed out that the art market tends to promote surfaces and speedy image consumption over weighty material experiences of works.5 In the ceaseless flow of images that is the status quo today, painting often seems to belong to another age – slower, more material, more contemplative. It is, however, precisely this ‘slowness’ that seems to lie at the very core of its existence. In her book Slow Painting: Contemplation and Critique in the Digital Age,6 Helen Westgeest highlights how painting can function as a space for reflection and critical thought, in opposition to the overabundance of images that floods the digital age.

Within this framework, it is important to recognise that the painted works dominating the international market today do not reflect the medium’s vital essence but rather, and in the main, its ability to produce images of commercial value. A characteristic of this is that during Greece’s period of economic and social crisis, very few Greek painters openly turned their hand to socially- or politically-engaged themes. This absence of starkly ‘political’ works does not imply indifference; rather, it reflects the ways in which the medium has been detached from collective narratives.

In contrast to other artistic practices such as performance art or video art, which can function as direct social commentary in the moment, painting remains inward-facing, oriented towards form and personal experience. Its political dimensions are expressed indirectly, through how an image shapes visibility and perception.

Alongside this, a large portion of artistic production in Greece is aligned with the needs of a rapidly developing interior décor market – works destined in the main for hotels, bars, and restaurants; this leads to safe and familiar-feeling solutions. As such, painting finds itself trapped in something of a paradox: it remains dominant as a collector’s piece but is at once marginalised when it comes to academic interest.

This is where the discourse surrounding slow painting assumes meaning: situated at the polar extreme of scrolling and swiping, painting insists on the physicality of the viewing experience – on the need to stop, look, and spend time. A viewer’s relationship with a painting is never momentary; it is a process that demands presence, duration, and proximity (which accounts for why it is most difficult to ignore a ‘bad’ painting but quite easy to breeze past an indifferent time-based work of art).

Every image stows within it a performativity, since its surface – be it canvas or pixels – mediates the way in which we perceive the world. Since the invention of photography and, later, of the moving image, painting has functioned as a ‘visual intermediary’, allowing us to look at the world anew and reflect on how we see. Jonathan Harris explores this shift via the notion of a “scopic regime” – that is, the way in which we see the world “through representational ‘machines for seeing’ (such as cameras), and representational forms ‘for showing’ (such as painting).”7

Painting also retains an anthropological dimension, restoring the significance of the gestural, of materiality, of touch. In this age of intangible communication, traces left by human hand take on special weight; as noted by Leonardo Cremonini, “painting forces artists to become masters of craft, compelling the brain to work with the body”.8 Each brushstroke is unique – a rebellion against the repetition that characterises the mass-produced images.

In its ideal state, contemporary painting does not compete with the digital image; it observes and redefines it instead. Even when drawing its source materials or themes from fleeting images, such as reportage photography or pictures plucked from the internet, the process of painting slows them down and ponders them after the fact, transforming the ephemeral into lived experience. This is how slow painting acquires its political dimension: it resists the subsumption of every experience into the flows of digital spectacle, offering up a space marked by silence and absorption, a space of meaningful interaction with the image. The silence of the canvas is an act of resistance – a break from the avalanche of images. Slow painting is not simply an aesthetic standpoint; it is an ethical and epistemological proposition: that we might learn to look once more.

Characteristic examples of this approach can be found in the work of numerous contemporary painters on the Greek scene, such as Sasha Streshna, Vasilis Zografos, and Eirene Efstathiou. While their stylistic approaches differ, they share an unremitting focus on slowness and the essence of painting as a mode of experience.

Vasilis Zografos, Untitled, 2023

Οil on canvas, 120×110 cm

Courtesy of the artist

Sasha Streshna reworks historically charged images, many drawn from school history textbooks dating to the Soviet times in which her parents lived. Her recurring themes centre on colonialism, coercion, and political or gendered dominance. Through systematic allusions to art history, Streshna expressionistically recasts her materials, covering her initial iconographic sources and spotlighting the potency of this gesture as a political act.

Through the strict discipline of the easel, Vasilis Zografos creates works that bring the viewing experience back to the fore; his austere framing, the materiality of his brushstrokes, and his complex colour palettes intimate rather than explain, transforming the familiar into something nigh-on metaphysical. Drawing on the traditions of representational art, his output constitutes a characteristic example of how painting can be relevant today rather than simply topical, of its time rather than of the passing moment.

Similarly, Eirene Efstathiou reshapes fleeting images drawn from current affairs and archival materials into paintings; the deceleration inherent in this process reveals new readings of the source photographs and showcases the value of materiality and duration, bolstering the power of painting to forge relationships with, and engender contemplative experiences in the viewer. In a time when myriad images circulate at breakneck speed, when images are worn thin by this process and endlessly replaced, Efstathiou’s paintings transform the ephemeral into durational experience. The painting acts as a surface for memory – a place in which to gather, not a place from which to disperse.

In all three instances, painting functions as a ‘visual intermediary’, slowing down the viewing process to illuminate its material, temporal, and emotional dimensions, serving as a counterweight to the digital fragmentation of experience. By going beyond surface representationalism, it creates a space of silent discourse and inner absorption where forms, objects, and spaces can co-exist in indeterminate yet dynamic interaction. The surface of the canvas becomes a mise en scène of quietude and proximity that invites viewers to pause, observe, and reflect. Such works demand an investment of time, of course, by both their creators and their viewers, and do not lend themselves to swift consumption of the image. An inner stillness is required and, perhaps in the case of less conversant viewers, a gaze that will do the work of decoding.

At the end of the day, within an artistic landscape in constant flux, painting is not simply a mode of representation but a space for thinking the image through – a way of understanding not just what we see, but also how we see. In the digital age, painting reminds us that vision is never neutral – it is an action, a choice, time spent.

Eirene Efstathiou, Other Things Happen in December Besides Christmas 2, 2015

Screen print and oil on paper mounted on aluminum, 33 x 33 cm

Private collection

The Role of the Curator and the Shift from Painter to Visual Artist

[Lost in Curation]

As argued by Hal Foster, Benjamin Buchloh, and other theorists,9 the relative marginalisation of painting is rooted in structural changes seen both at the centres that formulate theoretical and curatorial frameworks, such as universities and art schools, and at major museological and exhibitionary institutions, such as art biennials. The focus of exhibitions has shifted towards works that demand spectacle or the experiential involvement of viewers. Within this framework, Buchloh has shown the ways in which painting has been diminished within the neo-avant-garde culture of the industry, while Foster notes that modern-day museums often operate as “containers” for spectacular spatial experiences in which painting – a medium that demands time, contemplation, and commitment – struggles to survive.

In any event, the iconomy of painting as a formal category within the framework of contemporary art belongs within the same cultural paradigm as the redefinition of the role of the curator from a purely organisational or institutional position to one incorporating a creative and theoretical dimension: the curator does not simply select works, but rather constructs entire narratives and experiences through the exhibition design, lighting, spatial flow, and choice of thematic sections, becoming – in essence – co-creator. The globalised art market, the major international exhibitions (the Venice Biennale, documenta, Manifesta, and so on), and contemporary art museums function as the arena in which curators show off their conceptual and creative status and prowess, while the high-society aspects of openings and events – as covered by the media, arts magazines, and the internet – have all heightened their visibility as influential individuals able to shape tastes and trends.

Politically speaking, increased funding from private sponsors and institutional stakeholders, competitiveness between museums, and the desire for ‘signature exhibitions’ have all bolstered the need for some personality behind the curatorial narrative, making the curator both intermediary and creator of the artistic experience. Exhibitions such as documenta X (Catherine David, 1997), or the articulation of thematically grouped rooms at Tate Modern, advanced this logic: works are not independent pieces of art but rather elements within an overarching ‘interpretation’ set by the curator. With its strongly self-contained, polysemantic presence and formalistic tradition, painting often resists the sweeping thematic readings and ‘conceptual coercion’ typical of large-scale institutional exhibitions.

In any case, the redefinition of the curator’s role is organically linked to a similar shift in artistic identity, in which identifying oneself as a ‘painter’ suddenly seemed limiting. The terms ‘visual artist’ or simply ‘artist’ were more in line with contemporary interdisciplinary practice. This linguistic shift is no accident; it expresses the fluid nature of the boundaries between mediums – the “expanded fields”, as per Rosalind Krauss,10 where traditional categories of art collapse. However, the broader term ‘visual artist’ comes at a price: it debases the material and historical identity of painting. Set within an institutional system that prioritizes projects, installations, and experiences, painting seems to lose part of the autonomy that was once its hallmark – not because it has stopped being current, but because the parlance and mechanisms that interpret it have changed. When painters, of their own accord, distance themselves from the term ‘painting’, why would curators lay claim to it? The result is that exhibitions often end up incorporating next to no painting, not due to some prejudice, but rather to a sense of unease with the medium in and of itself and with its significance in a world where images are everywhere but attentive viewing is rare.

The Greek Case: The National Museum of Contemporary Art, Athens | EMΣΤ

It goes without saying that – despite obituaries and predictions to the contrary, dating all the way back to 1839 and the declaration “from today, painting is dead” attributed to the painter Paul Delaroche in reaction to the invention of the daguerreotype – painting has never stopped recurring as a quite singular narrative thread within contemporary visual art, be it with the great painters of the postwar period, such as Mark Rothko, Francis Bacon, and Gerhard Richter, or with movements such as the Neo-Expressionists (including the likes of Georg Baselitz, Anselm Kiefer, and David Salle) and the Italian Transavanguardia (Francesco Clemente and Nino Longobardi, among others).11 But Greece also saw a blossoming of the painter’s easel: it was during this time that major Greek painters (such as Yannis Moralis, Nikos Nikolaou, Dimosthenis Kokkinidis, Ilias Dekoulakos, and Panayiotis Tetsis) took on much of the teaching at the Athens School of Fine Arts, with a generation of their students (including Yannis Psychopedis, Chronis Botsoglou, and Yannis Valavanidis) going on to take the reins, maintaining this through-line of painting instruction established at the school. The visual artists later dubbed the “Generation of the ’80s” trained alongside leading lights of the Greek painting scene, while many of this group (including Giorgos Rorris, Edouardos Sacayan, and Irini Iliopoulou) would continue their studies at the École des Beaux-Arts in Paris, in the studio of Leonardo Cremonini, and receive particularly strong institutional support from the National Gallery of Greece and its then director Marina Lambraki-Plaka.

Ilias Papailiakis

The portrait of P.P. Pasolini, 2015

Oil on canvas, 45 x 38 cm

ΕΜΣΤ collection

The Greek case illuminates the relationship between institutional policy and painting in a noteworthy way. The National Museum of Contemporary Art, Athens | EMΣT, was founded in the early 2000s,12 at a time when international trends had already turned towards new media – video art and installations. Its collection was built without a long-term acquisition policy in place, shaped piecemeal and determined by shifting curatorial and aesthetic priorities. As is often the case with institutions that lack stable funding, the collection reflects – more than anything – the theoretical frameworks and concerns of each period, rather than offering a cohesive narrative snapshot of Greek and international art.

Painting, while present, has a limited place within the collection. Most such works owned by the museum were acquired through gifts and bequests from artists and collectors, and only rarely through targeted purchasing. Thus, we find works by major Greek painters of late modernism – such as Dimosthenis Kokkinidis, Pantelis Xagoraris, Rena Papaspyrou, and Sotiris Sorongas – that entered the collection thanks to the generosity of the artists themselves or their heirs. It is telling that even artists honoured with solo exhibitions at EMΣT, such as Bia Davou and Chronis Botsoglou, saw their works acquired as gifts rather than purchased.

The very few purchases made during the museum’s first phase focused mainly on new media, following international trends of the time that tied ‘contemporary art’ to video works, installations, and conceptual practices. This was not an arbitrary choice; rather, it was an expression of this newly founded museum’s need to put itself on the global ‘contemporary art museum’ map, distancing itself from the arts discourse that identified with painting and its ‘national’ character. Painting – associated in the mindsets of many with fine art schools, academicism, and more traditional aesthetics – seemed to stand in opposition to rhetoric on what was truly ‘contemporary’ and ‘international’ at the time.

This means that, from its very beginning, EMΣT harboured an inherent contradiction: as a national institution, it had a duty to showcase Greek artistic production, yet also to define itself at odds with this output, adopting the vocabulary of the international avant-garde. Person-centric in structure from the start, the museum was shaped in accordance with the vision and priorities of its successive directorates. From its foundation to the present day, EMΣT has been headed by three directors – Anna Kafetsi (1997–2014), Katerina Koskina (2014–2018), and Katerina Gregos (2021 to date) – each of whom spotlighted different aspects of the ‘contemporary’. Under Anna Kafetsi, the museum formulated its theoretical basis, with an emphasis on international terminology for conceptual practices; a series of major exhibitions showcasing work by Greek painters were indeed presented, but the purchased works were almost exclusively conceptual in nature or multimedia in approach. Under Katerina Koskina, EMΣT was consolidated as an institution, adopting rules of procedure for its governance and moving into the Fix building (the museum’s permanent home), though operating on a stringent budget. The collection was enriched at this time by numerous donations, including works by younger painters (such as Ilias Papailiakis, Savvas Christodoulides, and Vasilis Zografos), but these paintings were often not representative of their broader output. Once Katerina Gregos took the reins, the museum’s policy on gifts and bequests was completely overhauled. The museum would now assert its right to play an active role in its professional affairs: introducing guidelines for the fair pay of artists, curators, and academics, setting strict criteria for the acceptance of gifts and bequests, and launching a comprehensive programme for the purchase of new works. Despite such initiatives, painting still has a limited presence in the collection: between 2021 and 2025, out of 104 works accepted as gifts, only five were strictly paintings; and out of 109 works purchased during the same period, only one was a painting.

This percentage share is no accident; it reflects both the circumstances in which the collection was built and the priorities of contemporary art, which often emphasise works as processes, experiences, or ideas. It is my personal belief that the limited presence of contemporary Greek painters’ output in the collection does not indicate an underestimation of the medium but rather reflects the strategic efforts of successive museum directorates to align EMΣT’s acquisition and exhibition policies with international trends in the field. As such, the selection of works is not solely subject to aesthetic or historical criteria but also to the ways in which the museum formulates its mission statement in order to maintain its institutional legitimacy within a globalised framework.

From this perspective, the lack of painting in the museum’s collection can be viewed through the prism of what is called ‘collection lag’ – the time gap that lies between active artistic production and its official incorporation by institutional bodies. In the case of EMΣT, this gap appears to be bigger than at other institutions: artists create works, but their acquisition by the museum is delayed, resulting in a collection that does not fully reflect current output, especially when it comes to those media that demand contemplative engagement and an investment of time, as is the case with painting. This does not signal a lack of managerial purpose or vision; rather, it is down to constantly shifting administrative and political circumstances, limited funds, and adjustments that a museum still finding its feet must necessarily make, not only in terms of its collection but also its identity.

The educational role outlined in the EMΣT mission statement is also a factor contributing to this orientation. The museum sees itself as an institution for the education and cultivation of the public, seeking to communicate the themes of its exhibitions in ways that are engaging and clear. Video art, installations, and photography satisfy this educational logic more directly since they possess a narrative immediacy that facilitates the conveyance of complex concepts such as modern state formation, animal justice, and technological alienation. Painting, on the other hand, is marked by an interiority and a meta-language that demand time and attention – an active viewing experience – in order to reveal the depths of its meanings. And while painting, as a medium, might be more familiar to non-specialist visitors, its language is never so direct or performative as that of new media, and this is why it remains at the margins of museological narratives that strive both for learning efficacy and to kindle identification.

Today, however, in a time when the image has become a ceaseless stream and materiality is lacking, the absence of painting from the EMΣT collection is imbued with new significance. It is not simply an institutional gap; rather, it mirrors the museum’s own worries and concerns: how to remain contemporary when the very notion of ‘contemporary’ is changing. As noted by art theorists such as Griselda Pollock and Alison Rowley,13 the term ‘contemporary art’ functions more as a museological category than as a historical designation – it is a label that embraces whatever is current, without clear temporal or conceptual bounds.

The history of EMΣT is, to a large extent, the history of an institution seeking to define what is ‘contemporary’ anew, within a field in constant flux. Perhaps, however, what is truly contemporary corresponds not to what is new but to what endures; not to spectacle but rather to substance. In a time where the image is an unending flow, painting, with its slowness, its materiality, its silent persistence – is making a return, not as nostalgia but as a form of resistance. Because, at the end of the day, to paint today means to insist that art, and the institutions that house it, can still look deeply – can see and not just seem.

This anecdote – featuring the Russian Futurist poet and playwright Velimir Khlebnikov (1885–1922) and the Russian avant-garde painter and founder of the analytical realism art movement Pavel Filonov (1883–1941) – appears in Nikos Pegioudis’ book Artists and Radicalism in Germany, 1890–1933, Leiden & Boston: Brill, 2025, p. 118.

Peter Szendy, The Supermarket of the Visible: Toward a General Economy of Images, New York: Fordham University Press, 2019.

According to “The Art Basel & UBS Survey of Global Collecting 2025” (https://theartmarket.artbasel.com – last accessed: 31 October 2025), “paintings remained the most-purchased medium and the largest by value, accounting for 27% of total fine art spending in 2024” – a percentage share that has remained consistently high in recent years.

Marie-José Mondzain, Image, Icon, Economy: The Byzantine Origins of the Contemporary Imaginary, Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2005.

Hal Foster, The Return of the Real: The Avante-Garde at the End of the Century, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1996.

Helen Westgeest, Slow Painting: Contemplation and Critique in the Digital Age, London & New York: Bloomsbury Visual Arts, 2020.

Jonathan Harris, “Introduction: Hybridity, Hegemony, Historicism,” in Jonathan Harris (ed.) Critical Perspectives on Contemporary Painting: Hybridity, Hegemony, Historicism, Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2003, p. 20. The term “scopic regime” was first proposed in the early 1980s by the film theorist Christian Metz to distinguish film from the theatre.

Leonardo Cremonini, in an interview conducted by Margarita Pournara for the Greek Kathimerini newspaper: “Modernity Is a Threat to Painting” (https://www.kathimerini.gr/culture/223456/h-neoterikotita-apeilei-ti-zografiki – last accessed: 31 October 2025). Quote translated from the Greek.

Hal Foster, “After the White Cube”, London Review of Books, vol. 37, no. 6, 19 March 2015; and Benjamin H. D. Buchloh, Neo‑Avantgarde and Culture Industry: Essays on European and American Art from 1955 to 1975, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2000.

Rosalind Krauss, “Sculpture in the Expanded Fields,” October, vol. 8, Cambridge, Massachusetts: MIT Press, Spring 1979, pp. 30–44.

Yve-Alain Bois, “Painting: The Task of Mourning” in Painting as Model, Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1990, pp. 229–244.

For details on the complex procedures that shaped the identity and mission of EMΣT, see: Tina Pandi, “From Foundation to Operation: A Short History of the National Contemporary Art Museum, Athens – EMΣT, 2000–2010”, in Areti Adamopoulou (ed.), Art in Greece: The Legal Framework after 1945, Thessaloniki: University Studio Press, 2024, pp. 191–221.

Griselda Pollock and Alison Rowley, “Painting in a ‘Hybrid’ Moment”, in Jonathan Harris (ed.), Critical Perspectives on Contemporary Painting: Hybridity, Hegemony, Historicism, Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2003, p. 40.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Anna Mykoniati was born in Oxford in 1980 and grew up in Toumba, Thessaloniki. For this reason, she has been described as an “up-and-coming” curator since 2005, when she began working at the State Museum of Contemporary Art in Thessaloniki – a status she has paradoxically continued to maintain while steadily ascending through the ranks of EMΣT, Athens, since 2015. She studied History–Archaeology (BA), Cultural Heritage Management (MA), and Art History (PhD) in Thessaloniki and Ironbridge, UK. She has curated exhibitions in Greece and internationally, including: The Science of Delusion: A Genius in Deceiving Europe, University of Vienna (2014); Thalassa: The Sea in Greek Art from Antiquity to Today, Shanghai Museum, China (2022); Graceland: The Triumph of an Uncertain Path, 8th Thessaloniki Biennale of Contemporary Art (2023); Malvina Panagiotidi: All Dreams Are Vexing, EMΣT (2024).