Participation.

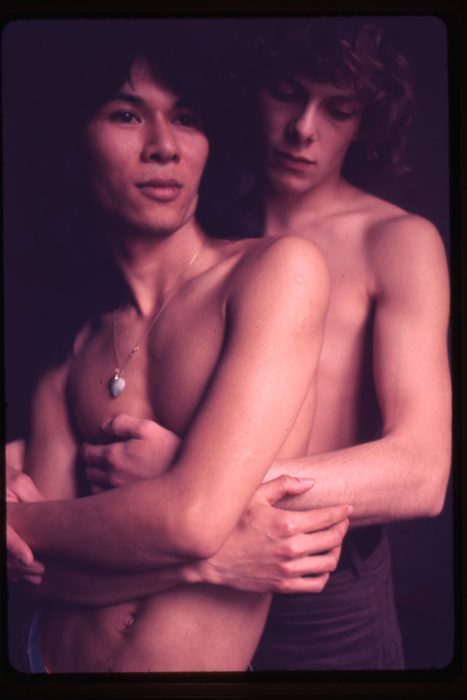

George Tourkovasilis, Untitled, n.d., digitised 35 mm slide

Courtesy of George Tourkovasilis Estate; Akwa Ibom, Athens; Melas Martinos, Athens; Radio Athènes, Athens

The Place as Context

In this issue, the magazine considers, among other things, the responsibilities of a national museum – in this case, a Greek one – to represent artists who are Greek or active in Greece. This theme raised more questions than answers for me. I wondered whether I really had a clear opinion on what the term ‘Greek’ means in the context of art, or who could even define it. The ‘expert’ seems to emerge precisely through the effort to provide such a definition – and it remains uncertain who, if anyone, can embody that role.

I left Greece to study in 2008 and returned in 2017. I spent my early adulthood between England and Lithuania, two places where I felt an unexpected familiarity – perhaps even greater than what I had experienced in Greece as a child or adolescent. This comfort may have stemmed from relative distance: I could not perceive their problems with the same immediacy, and even when I did, I did not experience them as my own. Until then, I had not questioned whether I belonged to Greece or whether Greece belonged to me, nor what participation or presence might actually entail. I allowed my preconceived notions of what the country chooses to cultivate institutionally to discourage me from asking these questions.

I viewed this ‘official’ Greece, i.e., the Greece of its institutions, evasively, with a tentative and somewhat immature gaze, unwilling to fully shoulder the responsibility for participation that my very presence implied. This participation involved not only me but also many of the artists with whom I worked and who were – and remain – active here. Instead, I oriented myself toward another Greece, one more accessible and familiar: Greece-as-place. A Greece that exists as an everyday circumstance for those who happen to be there, whether briefly or indefinitely – a place of unruly scope.

In this non-institutional Greece, a greater density of life converges, because it presupposes no fixed identity and therefore excludes nothing. It is here that its psychogeography unfolds and becomes more readily perceptible. In my mind, this Greece becomes tangible through images of Athens, where I have lived: broken sidewalks, pigeon droppings on the tarmac, bitter-orange trees, kiosks, pedestrian crossings that are rarely respected in practice, cars half-parked on pavements; images that seem ‘oldfangled’, as oldfangled as the word itself sounds.

Everyone who belongs to this Greece has experienced a personal version of it and carries their own constellation of references that form a landscape of belonging. Mine include the street racing on Lycabettus Hill, the hardware stores on Athinas Street, freddo espresso, souvlaki, the TV series Dio Xenoi and Eisai to Tairi Mou, the musicians Hatzidakis and Arleta, and the 50 Cent concert with Argyros at the OAKA in 2023. For Alexis, whom I met in Corinth, Greece-as-place also includes Tsitsopoulos playing from a JBL speaker at the Baths of Helen in Palaiopoli Beach.

The first images that come to mind are not necessarily the most representative. Reading my own list now, it feels saturated. Yet perhaps this saturation signals a kind of acceptance tied to the unruliness I mentioned earlier: an ‘answer’ that has not been subjected to the conceptual structuring such questions of national identity or institutional responsibility would demand. Even when the references of a group of people who have been here contradict one another, there is no need for mapping or negotiation. Every place, once condensed into words or concepts, carries a degree of cognitive dissonance. All these unmapped experiences with their nascent images compose a Greece-as-place that, as Halepas said of his Sleeping Beauty, “cannot spoil”. Wild and unbound by official narratives, it is not burdened by the responsibility of philosophical verification.

This Greece readily finds expression in art – art that does not require institutional recognition in order to exist, even if institutions later attempt to mediate or incorporate it. This art exists first for those who created and experienced it, and only then for those who encounter it. Perhaps we cannot yet call it ‘Greek’, since we have not defined what that would mean; but it is of Greece, or exists in Greece.

This distinction arises from the conception of artworks that do not set out to answer questions of national identity or national vision – even though they cannot entirely avoid them over time. Before turning to ethical or political considerations, it is more productive to understand that what may first appear to be a partial lack of self-knowledge is, instead, an alternative form of awareness.

Of course – and this is important to recognise – this perspective assumes a position of political privilege. It is not only a question of whether one is permitted to live in Greece (or anywhere else) but also whether one’s sense of belonging has remained intact, unchallenged, or unquestioned. Those who have not experienced such misalignment, who have not had to negotiate their identity, enjoy the privilege of not facing these questions directly. For many others, however, the experience of belonging is shaped by institutional constraints, social pressures, and constant negotiation.

This realisation should encourage us to cultivate a fidelity to the issue and to the repercussions of all possible experiences of this place we call Greece. Our political consciousness then stems from something foundational: empathy. These roles can easily reverse, and we could suddenly find ourselves confronted with these questions without our choosing. Yet in practice, sustaining empathy at all times is difficult. Much of life passes sideways, away from the centre of the question. Much of life – and much of art. Perhaps this is the kind of art that, while not explicitly addressing questions of national identity, often engages with issues of personal identity and autonomy, reflecting them indirectly through its content and language.

Art that emerges from an idiosyncratic, volatile, even solitary path is directly connected to this question. Institutional exclusion, particularly where identity is expressed, operates by mediating what it refuses to accept. Art, by contrast, accepts everything. Here lies a paradox. Imagine a museum that belongs to Greece – or exists in Greece – without being defined as Greek. Within such a space, art that does not directly address national identity can be presented freely. When this art carries Greece within it, or draws inspiration from Greece-as-place – not as a country or nation – the relationship remains multifaceted, even provocative, yet it neither defines the work nor reduces it to a tool for ideological purposes.

This perspective – like a photographic aperture shifting between blur and focus – allows us to maintain a fluid view of the landscape we observe or of the one in which we were born. It recognises value even in what has been shaped by corruption or inertia. I think, for example, of sidewalks which, through their dysfunctionality, present a peculiar, resilient anarchy. Yet they also bear something else: the finite, already-formed world we inherit and cannot bypass; an environment that precedes us and to which we must adapt, to manage, to make our way through.

Practically and morally, it would be appropriate to repair them; emotionally, artistically, and even poetically, their resistances remain generative. The coexistence of these opposing states gives rise to a mode of thought that accommodates the absurd and even the aggressive. Athenian sidewalks stunt movement, yet they also constitute a psychologically resonant system that mirrors human lawlessness and fragility in the face of death, love, and meaning. Walking on them reminds us of the persistence and resilience required to navigate them.

The analytical yet fluid gaze that approaches sidewalks and their disorder, recognising value even in dysfunction, does not remain purely theoretical. Sometimes one encounters a material confirmation of this sensation, a moment when theory, perception, and spatial experience converge.

The rusty topography of Christos Tzivelos

Christos Tzivelos, A voir, Windows on White, New York, 6–30 November 1985

Courtesy of Yannis Tzivelos; Akwa Ibom, Athens; Melas Martinos, Athens; Radio Athènes, Athens

One afternoon in 2017, I entered the Politeia bookstore and found the catalogue Modeling Phenomena published by the Benaki Museum in collaboration with the publisher Big Black Mountain The Darkness Never Ever Comes, dedicated to the work of Christos Tzivelos (1949–1995). Edited by Christoforos Marinos and Bia Papadopoulou – who also curated a retrospective exhibition – the catalogue and exhibition presented his work and activities in France, Italy, and Greece from the late 1970s until his untimely death. Tzivelos’ works struck me, and I felt an immediate connection with the book. His sculptures possessed a contemporary sensibility yet seemed to resonate with something Greek in an opaque but palpable way. They offered no overt narrative, but through their atmosphere and the interplay of material presence and emotional openness, they produced an indefinable imprint attuned to many elements of the Greek urban landscape. The rusty iron, the opalines, the subdued reds and yellows of his self-illuminated installations felt like extensions of roads – not as they now exist, lit by LEDs, but as they once were, saturated in yellow.

Tzivelos’ work was primarily site-specific, composed of installations that engaged in dialogue with – or functioned as containers for – self-illuminated elements. Plasterboards or expansive metal surfaces, often rusted, interacted with lamps that diffused light through coatings, initially wax and later resin. The wax coatings produced a thick yellow, while the resins, varying in thickness, yielded a spectrum of red hues. Collectively, the light orchestrated by Tzivelos – as recounted by Christoforos Marinos and Bia Papadopoulou – activated an alchemical palette of symbolism and atmosphere, giving form to the idea of transmutation.

Christos Tzivelos, A voir, Windows on White, New York, 6–30 November 1985

Courtesy of Yannis Tzivelos; Akwa Ibom, Athens; Melas Martinos, Athens; Radio Athènes, Athens

This activation was realised through an interaction with the architectural elements Tzivelos curated. Each installation – now accessible only through photographic documentation – presented a variable rationale: yellow projected onto rusty iron felt distinct from yellow on brick floors, different from red in the dark, and different from red on a terrace. Viewed collectively, these works enacted an organic meditation on spatial mutability. Some felt matinal and outdoors, others nocturnal and interior, and still others indeterminate, hybrid constructs, producing unfaithful spatio-temporalities. Their alchemy is most evident in these latter configurations, which inspire inventive departures from cynicism, fatigue, and indifference, replacing them with heightened vitality, emotion, and imaginative engagement.

Recent reports note that Athens has undertaken a comprehensive street-lighting upgrade, with 41,503 old fixtures replaced by modern LEDs, covering 95% of the municipal network. Last year or the year before, as part of this effort, the streetlights outside my house were replaced with cool LEDs (approximately 5500–6500 K). The couple across the street installed warm-light filters over their lamps, only to have them removed shortly thereafter – likely by the municipality – restoring the coolness of the LEDs that had been chosen for the street. This minor disagreement between private individuals and the municipal authorities, which essentially negotiates an aesthetic or emotional condition rather than something practical, brought me back to the work of Tzivelos. He grappled with such things, elusive yet intimately formative; phenomena that touch those who encounter his work unconsciously, and that resist reason. His artistic vocabulary was shaped by objects and trends commonly encountered in the Greek landscape: the prevalence of rust, the frequent occurrence of unguarded landfills, and the strong association of yellow light with the streets until recently.

These elements, of course, are not uniquely Greek. Argentine friends living in Athens often remark on a familiarity they perceive with the city; the same could not be said of Lithuania, for example. For Tzivelos, who had lived in Paris and Italy – places where similar material conditions were likely present – it is difficult to trace precisely where he encountered, introduced, or transformed these influences within his oeuvre.

2. Christos Tzivelos, A voir, Windows on White, New York, 6–30 November 1985

Courtesy of Yannis Tzivelos; Akwa Ibom, Athens; Melas Martinos, Athens; Radio Athènes, Athens

Another series of his works, consisting of opalines on which Tzivelos intervened with objects or stencils, and coloured lamps composing spherical projection screens or a form of shadow theatre, could be thought of as sculptural extensions of a cinematic experience. A Greek topography emerges in these installations, in the commonplace lamps that once populated arcades. Yet other geographies are integrated as well: elements derived from film noir, insects foreign to Greece, and other objects originating elsewhere.

Recently, while preparing an exhibition of Tzivelos’ work at Akwa Ibom – a space I run in Athens – which focused on another series of his works consisting of flashlights with painted slides, I had to find some industrial stools that Tzivelos used to stand the flashlights on, as well as a wooden chair that often appears in photographs documenting his installations with these works. Neither of these can be found in Greece, only in France, as I discovered along the way, a fact that connects this work specifically to another geography as well. This raises a question: should a French museum exhibit this work, or does a space, even one not formally linked to national identity, offer a more faithful, personal context?

I understand that this is also an institutional question, since funding often presupposes a connection to national consciousness and is derived from the citizens’ taxes. Ultimately, however, this does not answer the question of how geography relates to an artwork, or to a way of thinking.

Similarly, defining official art history in relation to personal art histories – composed of idiosyncratic references and markers that vary from one individual to another – remains challenging. Platforms like ISET1 provide invaluable tools for mapping these personal trajectories, revealing patterns such as periods of inactivity among artists, often disproportionately women. This is also where the issue of viewing, exhibiting, and publicising a work in relation to a more private and unseen production (which can be equally important or active) begins to take shape.

George Tourkovasilis: archives of intimacy

George Tourkovasilis, Untitled, n.d., digitised 35 mm slide

Courtesy of George Tourkovasilis Estate; Akwa Ibom, Athens; Melas Martinos, Athens; Radio Athènes, Athens

In 2020, collector Kyriakos Tsiflakos introduced me to the late writer and artist George Tourkovasilis. Tourkovasilis was best known for The Rock Diaries, a book that captured the rock and punk scenes of the 1980s in Athens in text and photographs, and for Kostas Chronas’ Motorcycle Rites, to which he contributed photographs depicting illegal motorcycle races in Keratsini. He was also known, to a certain extent, for his role as Yannis Tsarouchis’ assistant. Yet much of Tourkovasilis’ artistic output remained out of the public eye, a partly personal choice but also most likely shaped by Greece’s inhospitality towards radically introspective, confessional work in the early decades of his career (from the 1960s to, possibly, the early 2000s). This was all the more true for work that, with courage, sensitivity, and observation, depicted a fluid sexuality, unbound by questions of gender; despite the fact that most of Tourkovasilis’ photographic production consisted of images of men or boys.

Beyond Tourkovassilis’ sexual preferences – which in a polarised context emerges almost as a position – in reality, the thousands of photographs he left behind are an organic, natural, and unfiltered extension of his life. They are not so much works of art in the sense of individual, consciously shaped objects, but rather fluid reflections of his everyday life, of time passing, and of a cyclical digestion and regurgitation of the external world. With the exception of a few, very limited, attempts at exhibition, Tourkovasilis kept this production completely private, or at least separate from institutions, in Greece but also abroad. Towards the end of his life, he expressed a tentative desire to share a limited part of his life’s work, yet hesitated to reveal the full scope or ethos of what he had produced, composed, or – like Tzivelos – transmuted over the years.

Visiting his archive a year after his death, together with Elena Papadopoulou and Andreas Melas, we became both audience and witness to his expansive gaze, a personal universe continually expanding beyond what we could have fully imagined. A universe that transcended any text or photograph that Tourkovasilis had shown during his lifetime, either in exhibitions or through friends. Tourkovasilis’ photographs captured moments of tenderness, of fleeting beauty. They oscillated between close friendship or romantic connection and the recent or temporary intimacy that photography allowed him to create with strangers he met on the street. His lens became a conduit for connection, encounter, and exploration – always in service of a heightened attentiveness and an almost devotional attitude toward beauty in all its manifestations. In the margins of these works – less pronounced than in his more sociologically oriented projects – Greece appears again, and of course, France, where he lived for many years, through fashion, topography, and light.

Greece constitutes the landscape within which Tourkovasilis’ life and work unfold. Only upon careful consideration can one discern Greece as a country, a political regime, or as a culture (as in his depictions of Sotiria Bellou and Athanasios Veloudios). Through this distinctive interplay between private and public, Tourkovasilis’ silver-gelatine prints record many of the most vital moments of the post-dictatorship era, and Greece emerges as an inseparable frame to an otherwise recalcitrant thematic intention. The Greece of its institutions thereby encompasses Greece-as-place, and Tourkovasilis’ Greece as he alone experienced it; the two intertwine, coexist, and become indivisible. Perhaps one enriches the other, but institutional is neither automatic nor guaranteed.

So, is Tourkovasilis a Greek artist? In one sense, yes; in another, no. His work was the ritual of his life, the language he had developed to communicate with his environment. This language was not Greek nor the ‘language of photography’ in any generalised sense. It was his own: a personal idiom in which one may discern affinities with artists such as Peter Hujar or David Wojnarowicz, Sherrie Levine or Richard Prince (as George often rephotographs), yet whose core remained a singular, wholly personal frequency: his echo. We can now attempt to reveal it, or simply to show it as it was. His friends, family, and those who knew him – and whom we ourselves may never know – keep that frequency alive. Through them, Tourkovasilis can still be heard. But none of us can know which narratives he might have chosen for his work, beyond those he himself recorded; and even those writings belong to their own time.

George Tourkovasilis, Untitled, n.d., digitised 35 mm slide

Courtesy of George Tourkovasilis Estate; Akwa Ibom, Athens; Melas Martinos, Athens; Radio Athènes, Athens

George lived in England and Paris, travelled to New York, and ultimately only he could say where he belonged – if he belonged anywhere – or which of these places truly belonged to him. Only he could say where he felt freest, most loved, most alive. In Greece? Or in episodic moments shaped by other demands?

Over the past year, working in the archives and looking at George’s prints, I have often felt grateful. It moves me that an entirely personal and self-referential process has, without intending to, become a kind of personal gift: the ability to walk through Greece of the 1960s, 1970s, 1980s, 1990s, 2000s, and 2010s, until 2022, where I encounter myself again. I imagine that many who share experiences of this place will feel something similar, and in this sense, a museum can address the reflection produced by Tourkovasilis to them as well. Perhaps this shared experience, however difficult to define, is something we can more directly measure as relevant to the audience here.

Yet people are not bound only by such commons. The forces that connect us – to art or to one another – are more amorphous, more indistinct. History abounds with examples of unexpected affinities that suggest that the question of what ultimately concerns an audience – or a museum, which consists of a constellation of very different people – is not ‘what the audience is about’, but rather ‘what the museum can cultivate and inspire’ in an audience. Something need not be familiar, local, or aligned with pre-existing references to matter. Who decided that only what represents us concerns us? More often, we are changed by what is new, unfamiliar, and mysterious.

The writer Virginia Woolf and the garden designer Vita Sackville-West inspired one another for years through their correspondence. For whom, ultimately, is this archive of writings intended? English writers? English garden designers? Enthusiasts of literature or horticulture? There is no single answer; it is for those who happen to find it meaningful. A museum’s focus becomes clearer and more consequential when it is not constrained by such questions, but instead reflects the interests of the people who shape it at any given moment, always with respect for the public and with a willingness to inspire connection.

Sackville-West created a special area in the Sissinghurst garden inspired by the Greek islands – specifically, Delos, which she visited in 1935 with her husband. There she attempted to recreate a Mediterranean sensibility through plants, stone, and elements evocative of ancient ruins. Edward Leedskalnin, a Latvian immigrant to the United States, constructed “Coral Castle”, a hybrid garden and fortress dedicated to the “Love of His Life”, a much younger woman who refused to marry him. Wounded by her rejection, he devoted decades to creating this unique limestone monument as a personal expression of his unfulfilled desire and love.

What do these two gardens have in common? Beyond geography, that is. And how many other gardens – or non-gardens – might we imagine? For every taxonomy one might propose, another exists with a different axis. It is not only the national axis that proves inadequate or unnatural; every thematic axis inevitably limits the reflection of a far more labyrinthine reality. After all, language – even artistic language – is an abstraction. This should not constrain us; we can pursue each abstraction in parallel. But I do not believe that these abstractions, or the axes they produce, are subject to any obvious hierarchy, nor that a museum should be either.

Beyond the narrow confines implied by such questions, there are exhibitions, assessments, and theoretical explorations more attuned to this epistemological limitation. And they often arise organically: through interpersonal connections or through our relationships with landscapes. In Edward Krasiński’s apartment in Warsaw, inherited from Henryk Stażewski, one finds, among Krasiński’s own works, an installation by Daniel Buren – white and coloured striped bands placed on the windows, altering light and space, creating a dynamic interplay with the everyday objects Krasiński had integrated into his home. Under Soviet rule, when public art spaces were limited and monitored, this studio became a refuge for experimentation, hosting both local and foreign artists such as Lawrence Weiner, Emmett Williams, and Christian Boltanski, as well as directors, playwrights, and performers. The studio thus became a meeting place, a living forum for dialogue that transcended national and ideological boundaries. Krasiński’s horizontal blue line, running through the space at a fixed height (I think of the heart), now serves as a subtle but persistent reminder of this continuity: a space where relationships between ideas and people transcend time and borders, forming an alternative, living map of connection.

On the day [Mikis] Theodorakis died, I went hiking in Drakolimni – another Greek landscape. On the way, I found a stone at a high altitude, near the refuge, on which someone had written R.I.P. Madclip. Madclip had also died on the same day. Theodorakis’ Greece and Madclip’s Greece coincided; they shared the same anniversary and walked side by side. That stone on the mountain became, in its own way, an active museum. These two musicians shaped Greece-as-place in ways with institutional implications, but those implications do not encompass their entire significance. The complex worlds each represents – and the temporalities attached to them – seep into anyone who contemplates them.

This unexpected nature of our identities and their origins, which directly shapes our experience of art, resonates more with the global – with what exceeds national boundaries, with what is not confined by borders. Within this broad, unruly, and free framework appears the prologue to a museum truly in harmony with art, yet simultaneously asymmetrical to the world in which we live. By contrast, the national, institutional museum appears before us – like the sidewalk – as a pre-existing form: a necessary and practical construct shaped by current political conditions that render the national symbolically coherent today. The restrictive, utilitarian nature of such a museum inevitably alters the semantic hierarchy of the works it houses. It is essential to consider the responsibilities of such a museum, but we must not forget that this question is secondary to the experience of art itself – and, in a sense, stands in tension with its nature. So, whether this museum should present Greek artists, or artists active here, may have a simple, practical answer: ‘yes’. Yet at the same time, it brings to the surface a more difficult question: what does the question posed by the magazine cost us, and how does this discussion dislocate the space of art and the way it functions today?

Contemporary Greek Art Institute.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Maya Tounta is a curator and writer based in Athens and Vilnius. She is the cofounder and director of Akwa Ibom, established with Otobong Nkanga in 2019. Through Akwa Ibom, Tounta has curated exhibitions with artists including Rosalind Nashashibi, Thanasis Totsikas, Jason Dodge, Ellen Gallagher, Marina Xenofontos, Nicole Gravier, and Kostas Murkudis. Along with Radio Athènes and Melas Martinos, Akwa Ibom co-represents the estates of Christos Tzivelos and the archive of George Tourkovasilis. From 2021 to 2022, Tounta served as Art Director of e-flux journal. In 2024, she co-curated the 15th Baltic Triennial, Same Day, at the CAC, Vilnius. She is co-editor, with Helena Papadopoulos and Julie Peeters, of the monograph George Tourkovasilis: Strange Switch. Spent. The Night, Sleep (BILL, 2025), and, together with Tom Engels, co-editor of the exhibition catalogue 15th Baltic Triennial: Same Day (ROMA, 2025).